Forget technical debt

Revisiting a seemingly self-evident term

Forget technical debt

To be clear: I do not think we should actually forget technical debt. Also, this is not the nth post discussing if “debt” is an appropriate metaphor. I do not have a strong opinion regarding the metaphor. My point is rather that I realized in a recent discussion that in the end, it is not so much about technical debt but rather about something else, and I wanted to share the thought.

Thus, maybe a title like, e.g., “It is not only about technical debt but rather about many more things that have at least as much detrimental influence as technical debt, and technical debt is as much cause as it is effect which makes things even more complicated” would be more precise. However, while still not really nailing it, it would be a terrible title and probably cause more confusion than clarification. Hence, I decided to go with the simple, clickbait-type title and excuse upfront.

Therefore, sorry for the clickbait title!

With the excuse being made, let us dive in …

Measuring technical debt

A client recently approached me with the need to measure technical debt. They wanted to evaluate technical debt across their system landscape to steer their software modernization efforts more accurately. Sounds reasonable? Yup, it does. If we spend money on software modernization, let us invest first where it hurts most, i.e., where the return on modernization is highest.

As their system landscape consists of several technologies and programming languages, it was not clear if simply buying a tool would be an option. Tools that cover several decades of software technology and programming languages (which is the norm for all companies that exist for several decades) are rare – and if they exist and do what you are looking for, they tend to be very expensive.

Hence, they asked me if I could develop some useful metrics for technical debt which could be surveyed relatively easily, ideally automatically (and check in parallel if an appropriate tool at a reasonable price tag exists that could do the survey).

And so I started working …

What is technical debt, anyway?

While pondering potential metrics, I thought about concrete signs of technical debt. As basically everyone in software development talks about it, there must be lists with clear signs I can use to derive some useful metrics. At least I thought so. I did web research, looking through several definitions and articles – and did not find anything that helped me with my task.

All those articles defined the term in a more or less abstract way. They usually also described some drivers of technical debt and some general ideas on how to reduce it. But they failed to give me a concrete list of debt signs I could use to derive some metrics.

I found that somewhat strange because wherever you look, you see people talking about technical debt. Hence, one would expect there to be a clear catalogue of technical debt signs, like there are design pattern catalogues and alike. However, at least I did not find any. It felt a bit as if technical debt is primarily used as a sort of generic call to action (“We need to reduce technical debt”) or a non-assailable term to degrade something (“This program is full of technical debt”).

Or maybe I looked in the wrong places. Either way, the research did not really help as it did not bring anything that helped with my task. Hence, I decided to start over from first principles.

What do we want to achieve?

When starting from scratch, I began with the question: “What do we want to achieve by reducing technical debt?”

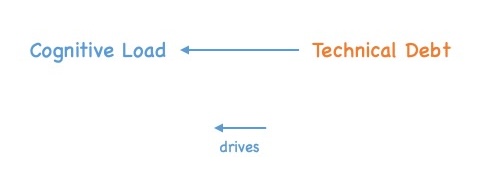

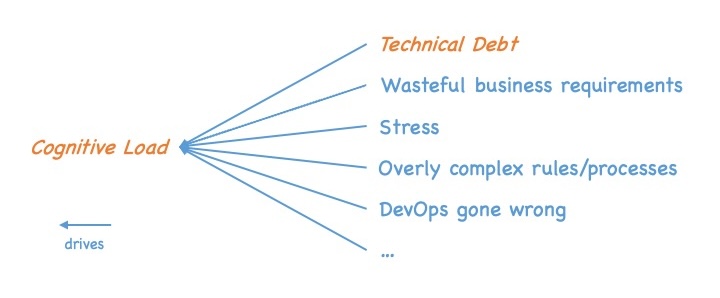

If we ponder this question, we quickly realize that technical debt is about cognitive load. Technical debt increases the cognitive load of a software engineer. The more technical debt a system contains, the harder the code becomes to understand, and the more different concepts, hacks, and alike engineers must keep in their heads whenever they try to implement a change or add something new. In other words: increased cognitive load.

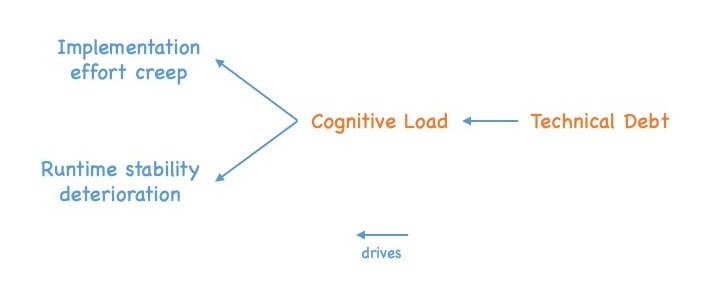

However, cognitive load is not the end of the line. Reducing the cognitive load of an engineer is not an end in itself. If we ponder why reducing cognitive load is desirable, we end up with two primary goals we try to support by reducing cognitive load:

- At development time, we want to keep the effort needed to implement a given requirement as small as possible.

- At runtime, we want to minimize the number of issues and failures due to bugs in the software.

If we increase the technical debt of a system, it increases the cognitive load of the developers working on it which in turn has detrimental effects regarding our primary goals:

- Implementation effort creep – The effort needed to implement new requirements increases.

- Runtime stability deterioration – The number of involuntarily introduced bugs that slip into production increases, which leads to more issues and failures in production. 1

This creates a sort of dependency graph that looks like:

Technical debt -> Cognitive load -> Implementation effort creep/Runtime stability deterioration

with the arrows meaning “drives”.

Looking in the opposite direction

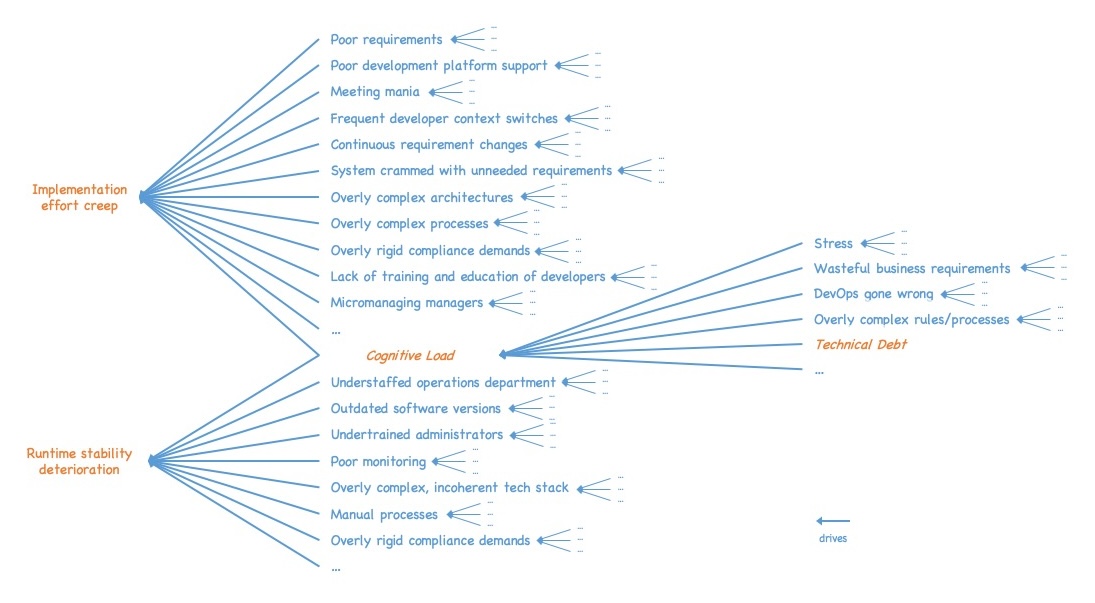

Up to this point, we found a causal connection from leading from technical debt to the actual goals behind the idea of reducing technical debt in software systems. But how about the opposite direction? Which kind of graph do we get if we start from compromising the two primary goals and look in the other direction? Do we get the same simple graph leading to technical debt with a “stopover” at cognitive load? Or does the resulting graph look different?

This is where things start to become interesting.

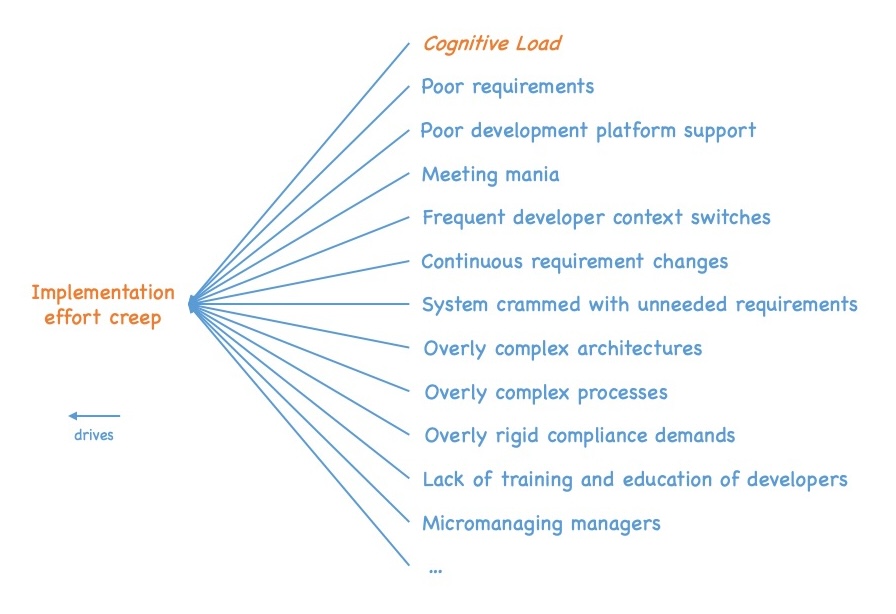

If we look at drivers of implementation effort creep, we immediately see a bunch of drivers, like, e.g.:

- Poorly written requirements

- Poor development platform support

- Meeting mania (very widespread in many companies)

- Developers split up between different projects requiring frequent context switches

- Frequently changing requirements while the implementation is already ongoing

- System crammed with unneeded and unwanted requirements due to a lack of effectiveness (see, e.g., my “Forget efficiency” blog post for more details)

- Overly complex architectures slowing development down

- Overly complex processes slowing development down

- Overly rigid compliance demands, constraining developers too much

- Lack of training and education for developers

- Micromanaging managers, preventing any flow

- Etcetera

and of course increased cognitive load.

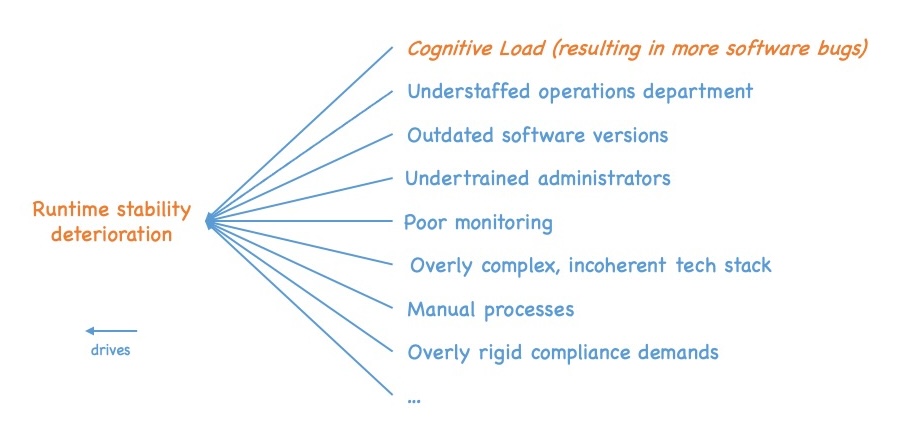

We see a similar pattern if we look at runtime stability deterioration, e.g., we see drivers like:

- Understaffed operations department

- Outdated platform and infrastructure software versions

- Undertrained administrators not really understanding their platform systems

- Poor monitoring letting easily detectable errors slip through

- Overly complex, incoherent tech stack that has grown over the years

- Manual deployment and administration processes

- Overly rigid compliance demands, constraining operations too much

- Etcetera

and of course an increased number of software bugs due to increased cognitive load.

We realize we do not have a simple line going from compromising the two primary goals to cognitive load. Instead, we see sort of a whole driver tree emerging, with cognitive load just being one of its leaves.

If we dig one level deeper and look at the drivers of cognitive load, we immediately realize that the tree fans out even further. A software engineer’s cognitive load can be increased in multiple ways, not just by technical debt.

Just to give a few examples:

- Wasteful business requirements, i.e., requirements that turn out not to be needed or wanted by the users, increase the cognitive load of the engineers. They also need to understand the code that implements such requirements and to program around it. Looking at studies that show that non-valuable requirements, i.e., requirements not creating business value (idle performance) or even destroying business value (value-reducing performance) make up 80%-90% of all requirements in the average company, and also looking at the fact that those requirements typically are never removed from the code once they were implemented, we can conclude that wasteful requirements are a much bigger driver of cognitive load than technical debt.

- Another big driver of cognitive load – or to be more precise: driver of reduced cognitive capacity – is stress. Stress triggers the fight-or-flight mode in our brains. In this mode, our mental processing capacities are massively constrained. As a consequence, the same task will cause a much higher cognitive load due to reduced processing capacity if executed under stress than if executed without stress – resulting in more time needed to implement it and a higher likelihood of errors. As most companies nurture an atmosphere of urgency paired with scarcity, resulting in continuous high levels of pressure and stress, it is likely that reducing the stress level (not only) of software engineers would have a much higher positive effect on the actual goals than reducing technical debt.

- Overly complex rules and regulations, e.g., coming from processes, enterprise architecture, compliance, or alike that force engineers to keep an abundance of dos and don’ts in their brains while trying to do their work, increasing cognitive load.

- DevOps gone wrong, which manifests in various forms such as NoOps, the absence of platform teams, or dysfunctional platform teams, forces developers to consider infrastructure components and their complexities, preventing them from concentrating on software development. Again, increased cognitive load.

And so on. Again, we see a whole tree of drivers emerging from the branch “cognitive load”. Without repeating the exercise for the driver siblings of cognitive load or the driver siblings of cognitive load, it becomes clear that we end up with a whole driver tree, not a single line, and that technical debt is just one of the leaves.

Thus, if we want to reduce implementation effort creep and runtime stability deterioration, solely looking at technical debt is not enough. Technical debt is just one piece of the puzzle (or rather: leaf of the tree). Even if we ensure that our systems are completely free of technical debt, we could still be stuck in a state where implementation is very slow and runtime stability is poor due to other drivers.

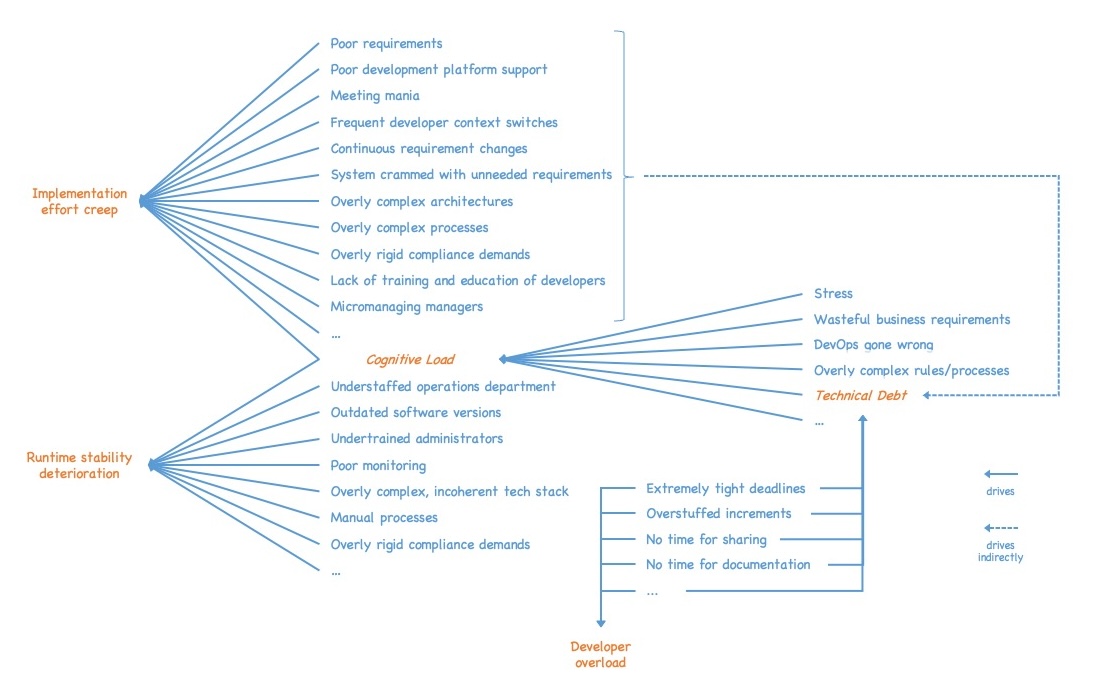

Looking further down

After that realization, I asked myself what drives technical debt, i.e., I wanted to look further down the tree. Here, I also realized something interesting. The drivers were basically split into two categories.

The first category is basically the same drivers that lead to implementation effort creep. These drivers have an immediate and a delayed effect. The immediate effect is implementation effort creep. The delayed effect is an increase in technical debt due to a declining focus on the solution and its quality. Additionally, many of those drivers also increase the cognitive load of software engineers, which reduces their focus on the solution and its quality as well, again resulting in increased technical debt.

As a side effect, we realize that our nice tree starts to evolve into a quite complex dependency graph with lots of cycles and mutual dependencies. We also see that many of the additional drivers also influence technical debt, which reinforces the prior observation that managing technical debt alone is not enough. Reducing technical debt is not sufficient with respect to our overarching goals of reducing implementation effort creep and runtime stability deterioration. Additionally, we will not be able to bring technical debt down if we do not successfully keep the other drivers in check.

The second category of drivers of technical debt has to do with developer overload and its negative consequences, like, e.g.:

- Extremely tight deadlines forcing developers to compromise quality

- Overstuffed development increments forcing developers to compromise quality

- Lack of time to document or share relevant information between development team members (often due to overly tight deadlines or overstuffed development increments)

- Etcetera

Oftentimes, the drivers of technical debt are reduced to this category. While these drivers are powerful drivers (in a negative sense), it is important to realize that those are by far not the only ones that drive technical debt.

Why do we limit our perception?

The question I asked myself after seeing this picture was: Why do we limit the discussion to technical debt in the software engineering community so often? I mean, it became obvious that simply trying to reduce technical debt will not improve the situation. It only has a very limited impact on the actual goals being implementation effort creep and runtime stability deterioration. And if we do not keep the other drivers discussed in check, technical debt will build up faster than we are able to reduce it. Additionally, why do we focus so much on developer overload when discussing the drivers of technical debt while ignoring all the other drivers?

I find these questions puzzling, and I think finding a good answer would help us to improve the impact of our work significantly. Unfortunately, I did not find a perfect answer, as this is a complex issue.

But I can offer a (hopefully) educated guess. I think we often limit discussions in the software engineering community to technical debt because it is the thing that immediately affects us negatively without any indirections, and we hence immediately recognize it .

Many of the other drivers lie outside our immediate perception. We may feel that they probably negatively affect us in some way, but it is not an immediate pain we experience.

Additionally, we may think those other drivers lie outside our area of influence and thus focus on technical debt because we have an idea how we could bring it down with our own hands. For most of the other drivers, it is not that simple. They are caused by other parties, and we do not have a say in how they should do their work. Therefore, I think we tend to focus on technical debt as this is what we immediately experience and what we could immediately remedy – if we would get the time to do it.

Probably the same is true regarding the question why we often solely focus on developer overload as driver of technical debt. This is what we suffer from on a daily basis. This is an extremely present adverse experience for most of us. Therefore, developer overload is often perceived as the predominant driver of technical debt, and we involuntarily miss all the other drivers that also drive technical debt – just because they are not that present.

Again, I am not sure if this explanation attempt really nails it. But even if not, I think there is a lot of truth in it. At least, it makes better understandable why we oftentimes focus so much on technical debt and miss the rest of the picture.

Now what?

The question is: What do we make with this insight?

We have seen that focusing on technical debt alone is not enough. It is just one of many drivers regarding cognitive load which in turn is just one of many drivers regarding implementation effort creep and runtime stability deterioration. Additionally, fighting technical debt alone is not enough because many other drivers drive up technical debt faster than we could ever bring it down.

My personal recommendation is that we still need to talk about technical debt. We need to make clear that it has a detrimental effect on those things that are most important for the people outside IT: implementation efforts and production stability.

But we also need to broaden the picture. We need to make clear what else affects implementation efforts and runtime stability. We need to discuss more holistically what is needed to improve the situation. We need to create awareness of how certain kinds of decisions and habits have counterproductive effects. 2

I know this is a lot harder and much more complex than just discussing technical debt. However, if we really want to improve our situation, I am afraid we need to take that route and broaden the discussion – including starting to have thoughtful discussions with people outside IT.

I hope I gave you some ideas to ponder. If you should have additional ideas that may help us to improve our situation (or at least make it better to grasp for those outside IT who often decide about our fates without understanding the consequences of their decisions), please do not hesitate to share them with our community. Things can only get better …

-

Even if hopefully most of the bugs are detected during QA (no matter if being done in conjunction with development or a separate phase), some bugs will slip into production undetected. And the more bugs are introduced at development time due to too much cognitive load, the more bugs will make their way into production. ↩︎

-

Side note regarding AI and the oftentimes made promise that it will solve all those issues by taking over software development: Simply adding AI without changing anything else will not solve the problems. Just adding AI-assisted or AI-driven coding without addressing the existing problems just reinforces the problems which is the opposite of what we want to achieve with AI. ↩︎

Twitter

Google+

Facebook

Reddit

LinkedIn

StumbleUpon

Pinterest

Email